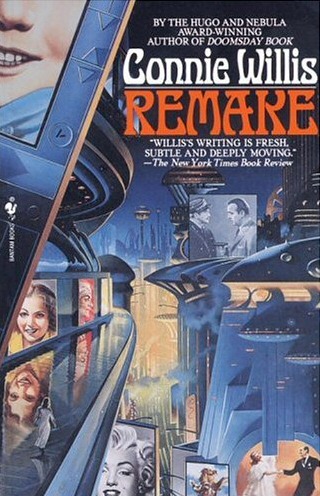

Extrapolating from the current intersection of Hollywood’s aversion to risk and its reliance on computer-generated effects, the future-fiction novel Remake (1995) dramatizes a film industry in which new live-action films are exclusively CGI-generated pastiches of old movies. Want to put yourself in a film and then change the ending? Just visit a video booth at Hollywood and Highland, and you can be the Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca who ditches Claude Raines and strolls into the mist with Ingrid Bergman instead. Such cinema revisionism—by fans and studios alike—is a juicy conceit, which Remake, at a brisk 176 pages, only begins to extract.

Tom, the novel’s protagonist, re-edits old films for a living, removing their references to “AS’s”—addictive substances, such as alcohol and cigarettes—a task reminiscent of Steven Spielberg’s gun/walkie-talkie swap in the DVD release of E.T. Rather than recapitulate the plot of Remake, I want to examine a scene in which Tom goes to an industry party and runs into a computer graphics tech named Vincent, who is demonstrating his latest breakthrough: a “weeper simulator” that digitally applies tears to any actor.

Tom, the novel’s protagonist, re-edits old films for a living, removing their references to “AS’s”—addictive substances, such as alcohol and cigarettes—a task reminiscent of Steven Spielberg’s gun/walkie-talkie swap in the DVD release of E.T. Rather than recapitulate the plot of Remake, I want to examine a scene in which Tom goes to an industry party and runs into a computer graphics tech named Vincent, who is demonstrating his latest breakthrough: a “weeper simulator” that digitally applies tears to any actor.

As Vincent explains, “Tears are the most difficult form of water simulation to do…. It’s because tears aren’t really water. They’ve got mucoproteins and lysozymes and a high salt content. It affects the index of refraction and makes them hard to reproduce.”

Tom watches a split-screen demo of various scenes comparing two forms of simulated crying: tears produced in front of the camera, and those generated by computer computations. Watching the famous Bogey-Bergman airport scene in Casablanca, Tom contemplates: “I looked at the screen. There were tears welling up in Ingrid’s eyes, glimmering like the real thing. They probably weren’t. It was probably the eighth take, or the eighteenth, and a makeup girl had come out with glycerine drops or onion juice to get the right effect. It wasn’t the tears that did it anyway. It was the face, that sweet, sad face that knew it could never have what it wanted.”

The observation resonates with a personal pet-peeve: technical verisimilitude is rarely the crucial value of aesthetic experience—contrary to relentless marketing in cinema, TV, and video games celebrating the latest advances in CGI, 3D, or physics engines. The unrealistic language attached to the industrial drive toward photorealism (“… My girlfriend won’t stop watching because she thinks it’s a movie,” as one regrettable PS3 ad boasted of Uncharted 2) is perhaps inevitable, but perhaps consumers—at least episodically—can see past these efforts in techno-utopian misdirection.

This is not to take a paradoxically Luddite position within new media studies. Technical prowess gives us new material from which to fashion convincing (even profound) narrative and ludic experiences of laughter and tears. But as Remake reminds us, the most compelling simulations of sorrow aren’t really about water.